By Amanda Petrusich

November 7, 2022

Source

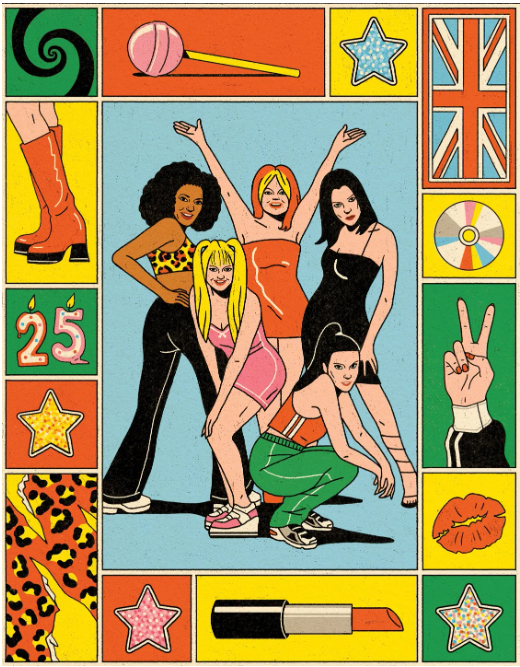

The Boundless Optimism of the Spice Girls

In 1994, Heart Management—the father-son team of Bob and Chris Herbert, with the financier Chic Murphy—placed a classified ad in the Stage, a British trade rag founded in 1880 and still devoured, more than a century later, by aspiring performers looking for a shortcut to fame. The producers were hoping to assemble an all-female pop group as a counterpoint to the windswept boy bands (Take That, Boyzone) then topping the U.K. charts. The scheme was not novel, or even particularly nuanced: a gang of cute, vivacious girls, some choreography, a few rousing choruses. “R.U. 18-23 with the ability to sing/dance? R.U. streetwise, outgoing, ambitious, & dedicated?” the ad asked. The trio auditioned some four hundred women, chose five, and soon decreed them the Spice Girls. The new group moved into a three-bedroom house in Maidenhead and began the sort of rigorous yet artless performance training that’s now a hallmark of the pop-band origin story. Each member (Melanie Brown, Melanie Chisholm, Emma Bunton, Geri Halliwell, and Victoria Adams, later Beckham) assumed a descriptive moniker (Scary Spice, Sporty Spice, Baby Spice, Ginger Spice, and Posh Spice). Chris Herbert, who was then just twenty-three, later spoke about the process as though he were creating a children’s cartoon. “The main thing was to get really good, sassy, colorful, bubbly characters,” he explained in the 2001 documentary “Raw Spice.”

In the summer of 1996, the Spice Girls released a début album, “Spice.” The dominant vibe of the boy bands of the time was a kind of grandiose romance: lovelorn bangers, sung by handsome men in loose-fitting blouses, making dramatic gestures with their hands. The Spice Girls’ first single, “Wannabe,” is a difficult track to describe, as it does not hew to any songwriting conventions, or to the laws of gravity. “They made all these different bits up, not thinking in terms of verse, chorus, bridge,” Matt Rowe, one of their co-writers, said later. “Just coming up with all these sections of chanting, rapping, and singing, which we recorded all higgledy-piggledy.” I was sixteen when “Wannabe” was released, and I recall being agog at the song’s lunatic pre-chorus, which contains a nearly Joycean meditation on desire:

Yo, I’ll tell you what I want, what I really, really want

So tell me what you want, what you really, really want

I wanna (hey!), I wanna (hey!), I wanna (hey!), I wanna (hey!)

I wanna really, really, really wanna zig-a-zig-ah.

There was no guise of seriousness, no pretense of circumspection, and certainly no saying what “zig-a-zig-ah” might entail. “Wannabe” is loud, pure, and giddy. In 2014, a team of Dutch research scientists suggested that it might be the catchiest song ever recorded. The track appears to include instruments, but whatever is happening musically is rendered irrelevant by the Girls’ bursts of jaunty rapping and hype-man whoops. The Spice Girls were not the most exacting performers, but they were brassy and buoyant. In the video for “Wannabe,” even Posh Spice—forever bedecked in a tiny Gucci dress and strappy heels, rarely smiling in photos—bounds around like a toddler who has got hold of some chocolate doughnuts.

In 1996, there was plenty of room on the pop charts for whimsy; the most popular song of the year was a bouncy remix of “Macarena.” In a few years, the Zeitgeist would bend back toward wounded male earnestness—Creed’s “With Arms Wide Open,” 3 Doors Down’s “Kryptonite”—but, for a brief moment, every time “Wannabe” came on the radio, life resembled a teen-age slumber party, where some intrepid attendee had pinched a bottle of peach schnapps, and there was a very long list of lame adults to prank call.

Though “Wannabe” had all the markings of a one-off hit, “Spice” generated three Top Five singles in the U.S., and the Spice Girls became a global phenomenon, preaching girl power—a vague marketing notion, even then—and a boundless, unquestioning jocularity. In 1997, the group released a second album, “Spiceworld.” It set a record for the fastest-selling album by a girl group, with seven million copies shipped in the first two weeks. The band travelled to South Africa to perform a charity concert, and met with Nelson Mandela. “You know, these are my heroes,” Mandela told a scrum of reporters. “It’s one of the greatest moments in my life.”

“Spiceworld” is now twenty-five years old. On the occasion of its anniversary, the album is being reissued with bonus tracks, B-sides, and live recordings from the band’s 1997-98 tour, all culled from the Virgin Records archive. The record includes both a demo and a remix of “Step to Me,” which was originally obtainable only by twisting twenty pink soda tabs off promotional cans of Pepsi and trading them in for a CD single, and something called “Spice Girls Party Mix,” a fifteen-minute medley of the group’s up-tempo hits, somehow made even more up-tempo. (I found it difficult to listen to without wanting to submerge my head in ice water, simply for the quiet.) The live material is more vibrant, though it might leave a listener craving lights, costumes, and dancing; the Spice Girls still work best as a multisensory presentation.

“Spiceworld” does not attempt to transcend “Spice” but, rather, to expand upon it in a lateral way. As recording technology has evolved, pop production has become more impermeable, and fingerprints tend to be erased or smoothed over. “Spiceworld” is the sort of pop record that doesn’t really get made anymore: sentimental, infinitely palatable, but also plainly imperfect, with wobbly vocals and canned backing tracks. None of these songs are especially adventurous. (The most stylistically ambitious moment on “Spiceworld” is the weepy breakup ballad “Viva Forever,” which includes a bit of flamenco-esque guitar.) The Girls’ limitations are still central to the record’s appeal.

From the start, the Spice Girls’ mission was to spread a kind of anodyne, generalized positivity; in 1997, this may have seemed like a timeless goal, but, twenty-five years later, it’s probably what makes “Spiceworld” feel the most dated. Naïveté of this sort is almost impossible to access now, in an era in which we are constantly reminded of suffering, both planetary and human. In the music video for “Spice Up Your Life,” the album’s first single, the Spice Girls steer a spacecraft through a post-apocalyptic cityscape. An icy gray rain is falling. Faces are wan, despairing. Prisoners nod off against the bars of their cells. The Girls sing:

When you’re feelin’ sad and low

We will take you where you gotta go

Smilin’, dancin’, everything is free

All you need is positivity.

The idea that optimism can undo despair is sweet, and maybe sometimes true, but it no longer feels like a very helpful message. Perhaps the group knew this then. As you watch the video, it’s easy to presume that the Girls are about to transform the streets with their upbeat attitudes, but the ship keeps simply drifting overhead. (It’s tempting to read this as a metaphor for futility, but to search too deeply for meaning is, of course, antithetical to the Spice Girls project.)

In 1998, Halliwell (Ginger Spice) departed the group, announcing, through her lawyer, “Sadly I would like to confirm that I have left the Spice Girls. This is because of differences between us.” The remaining members got to work on solo records. The band—without Halliwell—released a third and final album, “Forever,” in 2000. Since then, artists such as Adele and Haim have cited the Spice Girls as influential, and there are echoes of the group’s music in K-pop acts such as Girls Generation and Blackpink, and in so-called girl-boss feminism, in which the pursuit of power is reconfigured as righteous. But the band’s greatest legacy may be the way in which it encapsulated—possibly even dictated—the grinning innocence of the late nineties. Empowerment anthems, once omnipresent on the pop charts, have slowly given way to admissions of helplessness or self-incrimination; even Taylor Swift’s most recent single, “Anti-Hero,” contains a moment of radical self-doubt. (“It’s me, hi, I’m the problem, it’s me,” Swift sings.) In this way, “Spiceworld” is a comforting evocation of a bygone era, in which we could still declare ourselves magnificent without rolling our eyes. ♦